Coffin’ Up for Burial Options

Greetings, mortal friend!

When you die and require cremation or burial (a bit like the choice between chicken or veg on a South African Airways flight) - unless your culture has other plans for you, you’ll need a casket or coffin. This is when your loved ones will discover that here in South Africa, we really don’t have much choice.

Wood, veneers and reinforced steel remain the favoured local materials, while a bit of screen-hopping confirms that choice is restricted along a narrow continuum from ‘simple’ to elaborate, from 'less expensive' to 'outrageous' and from 'acceptable' to the kind of thing that would prevent your entry into the afterlife.

Overnight Caskets 'Praying Hands' Monarch Blue Finish With Blue Velvet Interior 18 Gauge Metal Casket

by Overnight Caskets, ON SALE NOW!

Despite the abomination above, a blend of eco-technological innovation, sensitivity to available space, cost-consciousness and environmental awareness have come to bear on the ‘death value chain’ and its associated rituals. Things are changing fast.

I also think that a profound shift in the ‘re-normalising’ of death is occurring, spearheaded by the ‘death positive’ movement and accelerated by the Covid crisis, which has encouraged people to reconsider received ideas about death and dying, including one-time use of expensive caskets. Likewise, people seem to be revisiting the importance of the rituals that accompany death, with so many of them having been ruptured or disrupted during lockdown.

A relative visits a cemetery in New Delhi during the Covid pandemic.

© Shutterstock/Explore Visuals

It feels like images of graves stretching into the distance have become so commonplace that they are losing their affective power. While I understand the editorial instinct for their use, I am becoming inured to them. Like other members of my hodge-podge hybrid South African consumer culture, mostly still riven with the fading remnants of Judeo-Christianity, I have to some extent been inoculated against grief and loss with a distancing dose of medical science and an overriding belief that death is actually optional, until it happens.

Although most of these images place death far away from me, I feel it is actually pretty close, and have never felt my mortality more keenly than right now. I am frequently encountering grief - to get a sense of the depth and scale of this, multiply each death by a factor of eight or nine. I wonder what this collective grief will foment in years to come?

A cemetery awaiting the tragically massive numbers of Brazilian dead in Sao Paulo, May 2020.

© Shutterstock/BW Press

Choices that need to be made by surviving family and friends can be very difficult. Some people however do possess the presence of mind (and enough distrust in others) to choose their own coffin or casket before they die – listen to funeral consultant Mark Wortman describe this in Episode 6 of How To Die, and Cape Town Director of Cemeteries Susan Brice filling you in on local burial practices and our worrying lack of space in Episode 2.

But let’s start with the basics. Is there a difference between a coffin and a casket, you ask? Well, yes – a casket has four sides, while a coffin is hexagonal, with six. Coffins (from the Latin ‘cophinos’ meaning basket) have an anthropometric shape, with a widening at the shoulders and narrowing at the feet – they were once referred to as toe-pinchers. The more euphemistically named casket avoids suggestion of the human form with a rectangular shape. They're also usually able to be opened on a central hinge for viewing of the deceased.

So now that you know, isn't it (not) quite exciting?

© quora.com

Either coffin or casket can also be called a pall, when used to transport a body, although this traditionally refers to a cloth that covers the box. And thus the term pallbearer, someone who carries the coffin, usually in a team of six. I mention this only for etymology nuts like myself, because ‘pall’ derives from ‘pallium,’ a cloak worn in Roman times, and interestingly also relates to palliate, as in palliative care – to ‘mitigate,’ which is then, literally, to cloak.

My own dear father, may he rest in peace, was forever shuffling his designated team of pallbearers, and after the occasional minor fracas on the telephone would be heard to erupt ‘That’s it! Colin’s out, Cecil’s back in!’ This would need to be written down in an increasingly illegible set of instructions for after his death, something that was in frequent focus due to his persistent heart condition and the knowledge that he could pop a gasket at any moment.

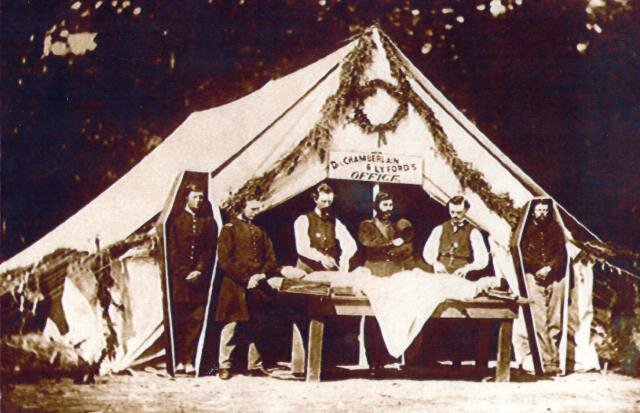

Introduced in the U.S. in the mid-1800s, caskets are much more of a one-size-fits-all vibe, as opposed to coffins which must be tailored. Caskets can be quicker to make, apparently. They came into their own during the American Civil War, when they were needed in large numbers (600 000 people died), and lots of bodies required quick transportation.

Perhaps you can see why coffins fell out of favour in the American Civil War.

Image: Uncredited here

In ‘From coffins to caskets: An American History,’ Sarah Hayes writes “It was the violence combined with the scale of death that led to the ‘the beautification of death’ in America during this period, and it was the shift in both name and shape of the coffin that was an effort to distance the living from the unpleasantness of death, and the hexagonal coffins were part of that distancing.”

You might therefore expect your friendly family undertaker to ask if you prefer a coffin or a casket. Jewish tradition meanwhile holds that no metal may be buried with a person, and hence you’ll find only simple wooden coffins with rope handles and wooden pegs in Jewish burials.

The earliest recorded use of wooden boxes for burial date from around 5000 BC in Shaanxi Province, China. Stone or clay, usually baked around the body, were more commonly used across Europe and Asia in ancient times, and then especially for nobility, for kings and chieftains and the like.

Closer to home, I’ve found it difficult to plumb African mortuary archaeologies for evidence of pre-colonial coffin use, and although entire hollowed wooden tree trunks have been used in some parts of the world, there is no record of this anywhere in Africa.

Tree-Coffin from the early mediaeval graveyard of Oberflacht, Germany

Image: Creative Commons Licence, by Andreas Franzkowiak

Note: I am not attempting an accurate historical account of burial in Africa! Besides, as stated by the editors of the Oxford Handbook of Archaeologies of Death and Burial, Liv Nilsson Stutz and Sarah Tarlow, “It is impossible … to draw out any meaningful generalizations from the huge variability of burial practices encountered through time and space across the [African] continent.”

Nonetheless, they provide some fascinating evidence of people being buried in ceramic jars in the western Sahara, and plenty of ornate burial chambers throughout other parts of Africa, usually tied to patriarchal hierarchies. Certainly, burial has always been locally ritualistic, and historically, seems to have also functioned as an opportunity to assert notions of kin, lineage, power and land ownership, to confirm social status, and most importantly, in the pan-African context, preserve the continuity between the living and the dead.

In this sense, the centrality of African belief systems relating to ‘Ancestors’ encourages the idea that comfort for those departing this world is paramount for their entering the next. What I have discovered in my amateur sleuthing is that coffins became widely available only in the 1700s due to a change in English law which had ramifications for English colonies and outposts, allowing ‘common’ people to use them, but I need to corroborate this. I guess coffins became the norm here in South Africa as well, as a departure from using cloth or some kind of equivalent to wrap bodies in simpler ways.

Coffins and caskets have gotten pretty ornate, as can be expected, I guess. An online search for 'African coffins' will result in a deluge of images of the Ghanain variety, popularised by Kane Kwei, a carpenter who started making his own custom 'fantasy caskets' in Accra.

Some things will kill you... ©ADAGP 2013

Kwei had been apprenticed to another local carpenter who had made a cocoa-pod coffin for a local chief. Allegedly inspired by this, when his grandmother died in 1951, he built her a casket in the shape of an aeroplane, and kickstarted a flourishing local industry that remains firmly within the ambit of quaint stereotyping wherever there's wifi.

Cheaper (well, not always, as you'll see) 'fantasy coffins' are the printed and personalized caskets which are now very much a big thing. So, would you like a casket emblazoned in knock-off Louis Vuitton, or do you wish to be known as someone who never had the chance to play for Liverpool Football Club? Both of these can be ordered locally and will set you back around... 65K. But if you're tight, relax, one can be hired for only 45K. Contact these guys.

What a bargain! Liverpool FC casket comes with a picture of Mo Salah at no extra cost!

Pics by Tumi Pakkies, IOL.

Seems like life’s infinite variety is represented in death too.

Nowadays, while so called ‘eco-coffins’ remain a niche offering locally, with a bit of cloth or cardboard, elsewhere wicker, rattan, mulberry pulp, banana leaf, bamboo, wool and cane are some of the things used.

A banana leaf, pandanus and rattan casket from ecoffins.co.

Interesting to me is the shift from a desire to ‘preserve’ the deceased in a metal coffin with sealing gaskets, to the idea of transforming the deceased and returning the corpse to the earth, the dust to dust cycle. In this respect, the hottest ‘new’ material to receive media attention as a coffin material is mycelium, the vegetative or thread like parts of a fungus, called hyphae.

The world’s first ‘living coffin’ is made by Dutch myco-savant, Bob Hendricx. The ‘Living Cocoon’ or Loop coffin accelerates decomposition and reintegration of human remains into the earth, requiring low-impact manufacture containing zero pollutants, and, through myco-remediation, actively removes contaminants from the soil, including heavy metals.

Do you want to be waste or compost? A side of the Loop coffin (which is actually a casket.)

To be honest, I think recycled cardboard does the same job? And it can also be impregnated with spores, which you can buy online.

Although the mycelium coffin accelerates things (around five years for full decomposition), it’s nowhere near as fast as the full-on composting of human remains that is now legal in Washington State, USA. Here it’s called ‘natural organic reduction,’ and for $ 5,500, after no less than thirty days, the compost that used to be your loved one is sent off to help regenerate a local forest, with a small bag provided for your own use.

Composting does away with the idea of coffins altogether, but it feels like we’re stuck with them for a while. Perhaps this is the ultimate solution?

In the meantime, why not make your own? I’ve found a strong tradition of exclusivity and marking-up the price of coffins and caskets, as they make their way from manufacturer to wholesaler to the funeral parlour. If you need them, you can find the handles and rails and things (called ‘coffin furniture’) online, and make your own, like the ‘coffin clubs’ that get together to do so in New Zealand.

Or if space is an issue, perhaps the most cost-effective bet is to make a bulk order of flat-pack cardboard coffins for you and your friends? Why not make it a weekend craft activity, and bring out the paints and glitter markers?

Next post will be all about new cremation options and cool things to do with the ashes ... but please do feed back about this article, especially if any inconstencies or inaccuracies are apparent to you.

Until next time, deo volente, go in peace, go in love -

Sean