Ghana Coffins

Ghana Coffins

What is the object that defines you?

An iPhone? Perhaps it’s a kitchen knife, a TV remote, a car key, a chocolate or a beer?

If you were Ghanaian, specifically from the Ga tribe, you might commission a coffin in the shape of your defining object from these guys - the original creators of what in the West are called ‘fantasy coffins’ but in Ga are referred to as ‘abebuu adekai’ - or ‘boxes of proverbs.’

Photo courtesy of Eric Adjetey Anang

The pictures of coffins below were sent to me by Kane Kwei’s grandson, Eric Adjetey Anang, who together with his father still works in the Kane Kwei workshop in Tishie, outside Accra. He is my guest on Ep. 33 - The Ghana Coffin Maker.

All photos courtesy of Eric Adjetey Anang.

Faces of Death, Faces of Life

Death Masks

Greetings, mortal friend!

So, ever been sent an unsolicited death pic?

I have. It was sent not long ago by the daughter of a friend, a picture of someone on her deathbed whom I'd come to know on the last leg of her earthly journey. We'd done a fair amount of laughing, sighing and shaking and nodding of heads together, and talking about the cancer, and the picture was intimate evidence of a life that was now finally over. It was sent with trust and love. Here she is, it said, but she's gone.

Lately it got me thinking about other images of the dead I've seen, specifically about death masks. The first time I heard about death masks was when I learnt that the one made from Cecil John Rhodes’ cooling visage had been stolen from the very room he died in, in what is now the Rhodes Cottage Museum in Muizenburg.

But one of the nifty things about death masks is that once an impression is taken, any number of casts can be made - some have become commercial items. An edition of Rhodes' death mask by the artist John Tweed sits in the National Portrait Gallery in London, donated by the artist in 1914. Although it was made on the 27th of March 1902, it looks like it could have been made yesterday.

C.J.R.

Image © National Portrait Gallery

It seems strange to see this powerful man, once celebrated, now reviled, at such close quarters. Can you judge a person by their face? I find the protuberant lower lip slightly unexpected, notice the architecture of the jowls and the serenely closed eyes in death, as well as the variegated geography of his brow. It’s almost like watching someone asleep, and slightly transgressive, this feeling of stumbling across someone’s face in private repose. The artefact comes skin-close to the life of a man whose breath has just left him forever. No wonder it was lifted by a thief. It feels like it exudes some kind of aura. I wonder where it is today?

Death masks seem to present a verisimilitude no portrait could express, in all the detailed contours they present. Take this one for example, of Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre, French statesman, lawyer and provocateur, a key figure of the French Revolution, who was beheaded in the Place de la Révolution on the 28 July 1794, aged 36. A harried man at the time of his death, executed in front of a large crowd, the mask somehow conveys a resigned sense of peace and beauty, I feel.

M.F.M.I. de Robespierre

Image from 25 Death Masks of the Famous and Infamous

Next up is not a death mask but a life mask, of Abraham Lincoln, made around five years before he died, in 1860, by Leonard Volks.

Able Abe

Image via Internet Archive

It's interesting to compare it with the one made just before he was assassinated, to see the visible toll his life had on him.

But there was something else going on - you'll notice a droop on the right hand side of the face, and a slackening of his lower lip. Modern doctors say this reveals something called cranial facial microsomia, and others, such as Dr. John Sotos, a cardiologist and rare-disease expert, go further, pointing to facial evidence of a rare, cancer-causing genetic disease called MEN2B (although this sounds like a silly male response to #MeToo). It is now believed by some that Lincoln would have died of thyroid cancer if he hadn’t been shot. (Modern day presidents like Mr. Obama, on the other hand, get to be 3-D printed.)

The poet John Keats, who died from tuberculosis two hundred years ago, on 23rd of February, 2021, aged only 25, is another example. An enamoured collector bought a death mask of his at an auction for £ 12,500 recently.

Death mask of John Keats

Picture by Nik Wheeler, Alamy.

A common use of death masks was to act as a kind of artistic biographical benchmark. In Keat’s case, two masks were made from the same mold made after his death, one of which was used by the artist Joseph Severn to paint a portrait. Although both masks were lost, a secondary impression was made by Charles Smith and Sons, of which an estimated nine copies remain. Keats also had a ‘life mask’ made five years before his death. Comparing the two, one immediately notices the physical wasting that accompanied his illness, and how much thinner his face is.

Life mask of John Keats

Picture: Murdo McLeod, The Guardian

Death masks seem de rigeur for a certain type of person at a certain time in history and were often used for posthumous portraits. Without any fanfare, a newspaper report from as far away as the Philadelphia Times that chronicled Rhodes’ death baldly states, ‘a death mask will be taken,’ as if this is a formality, in the vein of ‘regret no flowers’ at a funeral.

This is why images for any number of famous dead white men of yore are available online: Napoleon Bonaparte, Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson, Oliver Cromwell, Ludwig von Beethoven, James Joyce, Martin Luther… you get the picture. It’s like a type of morbid gallery, each of whom have their eyes closed. They can’t see you see them. (The biggest collection is the Laurence Hutton Collection of Life and Death Masks at Princeton University, which you can visit online.)

One of my favourite masks is of the outlaw Ned Kelly, whose violent life seems to so at odds with this quietened face, which still bristles with characterful evidence of a hard life.

Ned Kelly

Image from 25 Death Masks of the Famous and Infamous

Death masks can be hot property, and not just in Rhodes’ case. When Napoleon died (why on earth isn’t he just called Bonaparte? Don’t people like saying Bonaparte?), also two hundred years ago, incidentally, on May 7th 1821, even though he had been exiled and disgraced, those around him were quick to realise the financial potential a death mask might have for his many admirers.

His is one of the most prolifically copied death masks in the world, partially because of the fact that the surgeon who claims to have made it, Dr. Francesco Antommarchi (although he was challenged in court by Napoléon’s English Surgeon, Francis Burton, who claims Antommarchi stole a mask he had made for the Countess Bertrand) was an avid traveller who commercialised reproduction of the mask and took it with him all over the globe, which is why today, Bonaparte (I refuse to call him by his first name, it’s like referring to James Joyce as ‘James’) peers from countless bookshelves. Trouble is, there are at least eleven versions, with so many discrepancies, that the Fondation Napoléon in France has had to verify them.

The Bertrand-Malmaison Mask of Napoléon Bonaparte

Photo: Creative Commons License

Predating these distinctly life-like impressions, however, were death and funerary masks made for other purposes, dating back into early Egyptian times, when a death mask was deemed essential for any wandering spirit needing to locate the body it had departed from. In some African tribes, it is alleged that death masks endowed the wearer with the life-force of the deceased and was a powerful shamanic tool to maintain connection with the spirit world.

In the Middle Ages the ritualistic aspect waned and as technologies emerged which enabled faithful copies to be made, death masks took on a more secular aspect, both as a physiological record and physiognomic data, and as a way to display deceased people of renown to a curious public. Then too, before the invention of photography, death masks were apparently used by law enforcement agencies to record the physical traits of unclaimed bodies.

Two gentlemen preparing a death mask

Picture: Wikimedia Commons License

Like Bonaparte’s death mask, the American gangster John Dillinger's mask aroused great interest and skirmish. It can be studied on the US Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Artifact of the Month page, along with the death mask of fellow gangster Charles ‘Pretty Boy’ Floyd. Although the making of death masks had all but petered out by this time by the early 1930’s, it was still not uncommon.

Death mask of John Dillinger, on the FBI's 'Artifact of the Month' page.

Dillinger was shot and killed in what the FBI call a ‘confrontation.’ According to the FBI case files, “Every politician and his friend in Chicago crowded into the morgue for the morbid purpose of viewing Dillinger’s remains [....] Great confusion existed at the morgue for several days, inasmuch as there were thousands of people who attempted to gain admission to view Dillinger’s body.”

Police departments inundated the FBI with requests for copies of the mask, and once it was decided that this was too onerous, permission was given for trainee agents to make their own copies from the original while studying at the FBI National Academy, as part of a forensic modelling course, which is still in existence today. “As a result,” cautions the FBI website, “countless copies still exist and are sometimes auctioned online as originals.” Note the damage to the face caused by the ‘confrontation.’

Harold May of the Reliance Dental Manufacturing Co. at work creating the death mask of Dillinger’s face at the Cook County Morgue in Chicago to demonstrate the quality of the company’s plaster.

Picture: Chicago Tribune

Perhaps one of the most recognisable faces in the realm of death masks, not only incredibly popular in its day but also because her mask was repurposed many decades later, belongs to l’Inconnue de la Seine, or The Unknown Woman of the Seine.

This impression was apparently taken from the unidentified body of a young woman recovered from the Seine in the 1880’s, after news of her ‘euphoric’ expression spread all over the city and she'd become a popular fixture in the morgue, which was open to the public. (Any plans for the weekend darling? Should we take the kids over the the morgue?)

It is speculated that she was one of many sex workers who took their own lives by drowning. There is some doubt over this - some say it’s impossible someone recovered from the river would be in such condition. Nonetheless, provenance aside, the tranquillity of her features inspired many Parisians to reconsider the moment of death not as agony but as bliss, and her face became an influential ideal of feminine beauty, compared to the Mona Lisa.

According to an article about her in Wikipedia, the critic Al Alvarez wrote in his book on suicide, The Savage God: "I am told that a whole generation of German girls modeled their looks on her.... the Inconnue became the erotic ideal of the period, as Bardot was for the 1950s. She was finally displaced as a paradigm by Greta Garbo."

l’Inconnue de la Seine

Photo by Albert Rudomine, 1927

Her death mask was copied en masse and has sold extremely well and is still in production by Atelier Lorenzi of Paris, available for €156 at the time of writing.

And in an ironic twist, given her alleged origin story as a victim of drowning, she was both an obvious and a somehow neutral choice for the model of first aid mannequin Resusci Anne, a CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) doll still made by Laerdal (order one here) and used the world over since 1960, and is hence known as ‘the world’s most kissed face.’

Isn’t the internet amazing? One of my cherished sites of yore, when the ‘net was a different place entirely, was rotten.com, which shamelessly promoted itself as the ‘dark underbelly’ of the web. Alas, it is no longer. It took actual courage to click on a link here, after reading a description of the image – things like ‘unfortunate incident in a Tokyo train station.’ What you see you can’t unsee.

Still, it seems like images of death, as much as death itself, are taboo. It’s not done, to stare. I would hazard that many people have not seen a dead body. Why? Death is hidden and death is threatening. Yet death is inevitable and serves to sharpen an appreciation of life, in my experience. The photos I’ve seen online, mainly in the archives of American police departments of ‘John and Jane Does,’ unidentified bodies, attest to the fragility of life, how it is gone in an unexpected breath.

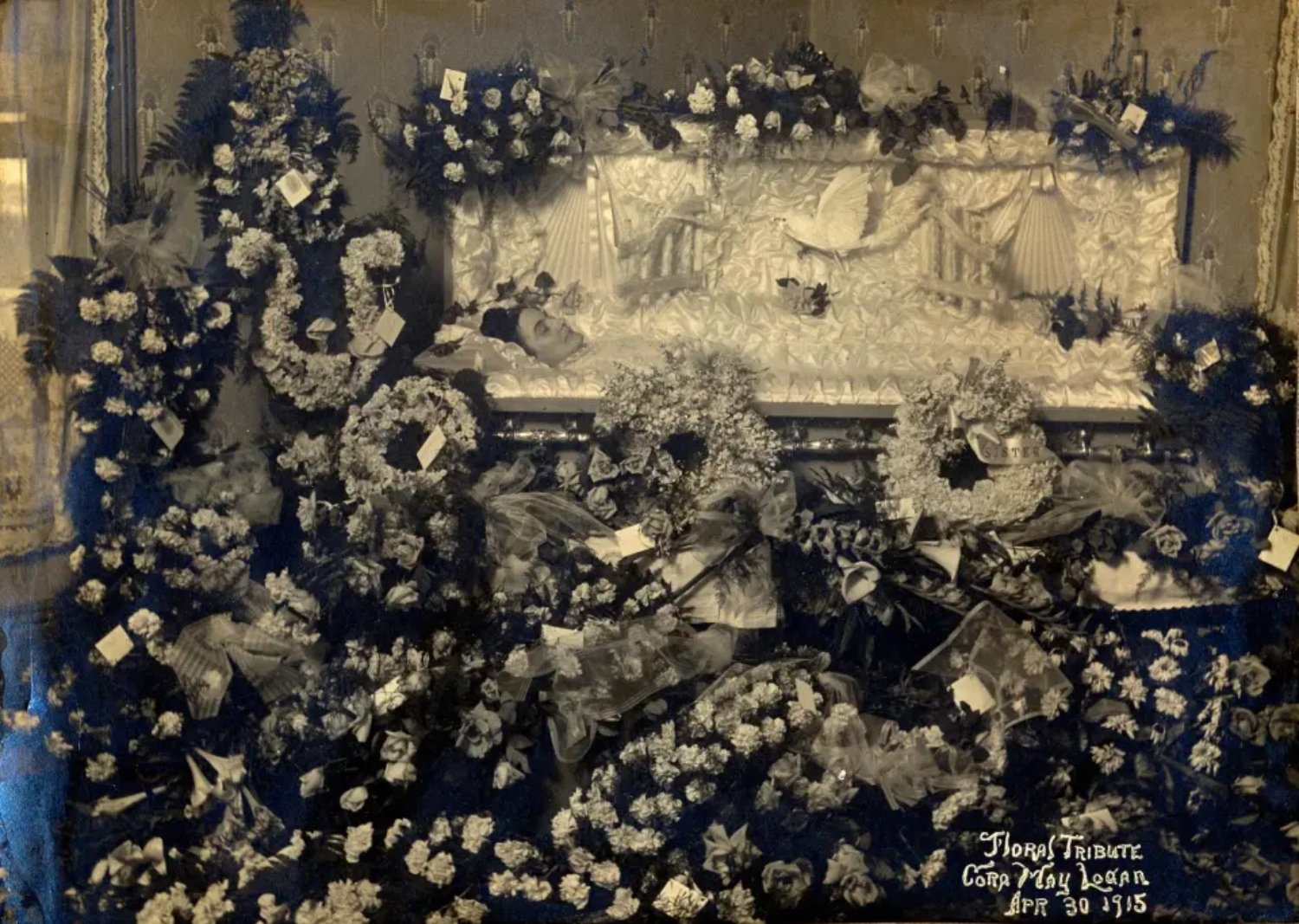

Although Covid-19 has, in my opinion, altered our relationship with death, in other times death might also have been more familiar, like during wars, for example. In the early days of photography, for instance, the Victorians used the nascent technology to capture images of their dead as a memento mori, a keepsake for the living.

For you to remember her by.

Photo Credit: News Dog Media

Still more eloquent is the fairly recent morgue photography of people like Jeffery Silverthorne, who visited the Rhode Island State Morgue in the 1970s. Then fast forward to today, when we have the iPhone and its ilk, ready for a quick and sometimes illicit snap at the deathbed. This too is testament to an evolving relationship with death, I feel, and perhaps allows us to share our grief. ‘iPhone Death Portraits’ occasioned a recent piece in the New York Times.

And finally, dear reader, if all of the above hasn’t quite quelled your morbid curiosity, you could always take a little browse through murderpedia, if you still have time on your hands – because none of us, after all, know exactly how long there is to go.

Choice, Death and Cremation

Greetings, mortal friend!

No doubt you're aware of the unfolding Covid-related tragedy in India and have seen images of cremation pyres extending beyond crematoria and into car parks and elsewhere. Delhi's largest crematorium, the Nigambodh Ghat, which used to require 6,000-8,000 kg of wood daily now needs 80,000-90,000kg - every day.

New Delhi, April 30 2021. A tsunami of death rages here, which Arundhati Roy describes with her trademark eloquence, courage and insight as a crime against humanity. Please consider donating to Medecins Sans Frontieres in India here to make a difference today. Image: Shutterstock.

Against this backdrop of smoke and political obfuscation, of bitter flames and exhausted ash, it may be opportune to look a little deeper at the ancient practice of cremation, favoured by Hindus, Jains, Sikhs and Buddhists for millennia, but seemingly detested by many others over the years.

It's not much of a choice though, is it - burial or cremation? But then, the idea of choice isn’t much associated with death anyway. We can't choose to die or not. It's a done deal. What sliver of choice we might have is to decide upon a healthier lifestyle with less risk. However, whether you smoke and drink or jog under ladders or eat your greens, the manner and the timing of your passing will be something which you have little choice over. No matter what you get up to, it seems, when and how you expire is decidedly uncertain, except in cases of tragic self-will.

Choices sometimes deepen divides with people we love.

Image from www.pipelinecomics.com, The Old Geezers Vol. 5

Even a healthier lifestyle isn't much of a choice, and besides, most people can't choose one anyway. For the most part then, death can visit at any time. On the way to the shops or on the way to the bathroom. Choice and death are only acquainted in macabre jokes and last meal requests from inmates on death row.

However, lack of choice doesn’t stop when we do, but extends beyond death too. For most followers of Islam, Judaism, traditional African religions as well as Christians of different stripes, inhumation (a fancy word for burial) is preferred, even mandatory, while cremation is strictly taboo. Why?

For these faiths, burning a corpse is understood to be a defilement of the body, which is regarded as the temple of God, a holy vessel animated by a divine spirit which departs upon death, perhaps to return. One does not tamper with God’s creation, is the prevailing belief. The prophet Mohamed taught that that to break a man’s bone in death is the same as to break it in life.

The body, made in God’s image, must therefore be kept intact for all sorts of afterlife activity. In an article called 'Cremation Threatens Zimbabwe's Ancestral Spirits,' former Vice-Chancellor of The University of Zimbabwe Gordon Chavunduka summed it up like this: “If the body is cremated, that spirit would be blocked. Although it would remain alive, it would be angered that traditional burial rites had not been followed properly and could return to punish the family and community.”

This is the story elsewhere in Africa too, writes Robert Mbaraga in an brief survey called 'Perspectives on Cremation in Africa' in the East Africa Times from Kenya. Local theologian Maake J S Masango acknowledges the same in ‘Cremation a Problem to African People,’ where he foregrounds the problem of dwindling space for burial and somehow makes a case for change, with Biblical reference.

'Manguang Metro running out of burial sites, encourages cremation.'

Photo: Matiba Sibanyoni, Reuters.

With not much land suitable for burial and sacred burial rites remaining inflexible, it’s urban planners and local government that are becoming vexed the world over, while no-one dares offend. Meanwhile, burial costs are rising. They're also considered vastly more environmentally damaging than cremation, even with tightened furnace emission standards.

In Beijing, for example, where cremation is highly encouraged, a grave plot costs more per square metre than an apartment. According to Wikipedia, in some German cities, gravesites must be leased, not bought, and bones disinterred and bundled up by a specialist when the lease expires, whereafter the information on the headstone is inscribed on the skull and placed into a crypt.

Susan Brice, Director of Cemeteries for the City of Cape Town, identifies lack of space as the biggest threat to the future of burial practices – same as it’s been for the last twenty years. (Listen to her insider perspective about death and burial in Episode Two of the How to Die podcast, and how this issue doggedly remains at number one spot on the agenda for each annual conference of the South African Cemeteries Association.)

Cape Town, by the way, has about a 20% cremation rate, and although I think this information is out of date, it's considerably higher than anywhere else in South Africa. Why? Lots of heathen ex-surfers, apparently, although Hindus, Catholics and Protestants are also quite happy to be cremated. The latter, especially, seem to have gotten their heads around the ‘from dust you came and to dust you shall return’ thing quite early, to include ashes, while the Catholic Church only sanctioned cremation as recently as 1963, although discourages the scattering of remains. For Catholics and many other Christians, and people in other faiths too, it seems that culture and class can play more of a determining role than faith in the decision to cremate or bury.

So says The Times of India.

But things can change and do. An interesting example is related in the consistently excellent 99% Invisible podcast, in an episode called Life and Death in Singapore. This tiny island, which takes 45 minutes to traverse in a car (with traffic, nogal) has a cremation rate of over 80%. But it used to be 10%, about fifty years before. So what happened?

In 1973, the Singapore government decreed there would be no more ground burial at over 70 cemeteries, due to lack of space for the living – the cemeteries were simply too big, some with gravesites thirty metres wide. Housing needed to be built, choices made, the living privileged over the dead. Over 100 000 bodies were exhumed and cremated from the largest cemetery alone, Peck San Theng, which was reduced in size to just eight hectares from an original three hundred and twenty four.

As you might imagine, this decision wasn’t widely welcomed, and although 50% of the interred bodies were claimed, then cremated and memorialised, the other half were not, and were cremated together and scattered solemnly at sea. (Perhaps this demonstrates that despite an avowal that burial is necessary, in many places, I think it’s a truism that graves tend to become neglected over time, within a generation or two, and then fall into disrepair. I think the German cities who lease grave space understand this.)

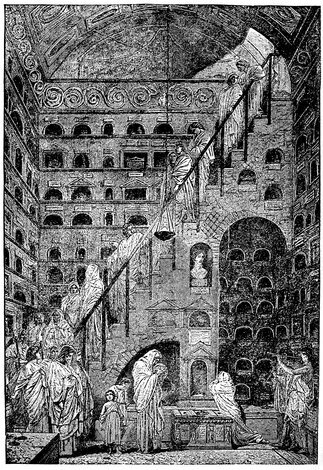

In Singapore, ancestor veneration was part of many religious practices on the island, which has been recognised as the most religiously diverse in the world. Here then, it seems that choice was once exercised, then bluntly removed. (Listen to the podcast for a fuller discussion of how things came to pass and the culture around cremation changed.) The remaining land in Peck San Theng includes a new columbarium – a building for funerary urns, which was without local architectural precedent. The same vigils and rites for the dead are now carried out in these narrow corridors just fine thank you.

Peck San Theng columbarium. Photo by Katie Thornton from 99% Invisible.

Incidentally, in 2007 the Singaporean government sorted out burial problems at the remaining state-run cemetery where inhumation was still permitted. Buried people are interred in a grid-like set of crypts which must be evacuated after 15 years, consistent with the Islamic practice of recycling graves, whereafter remains will commingle.

This is similar to practices in modern Greece, where you have to pay good money to keep people in the ground, and exhume at your own expense too. The first and only crematorium in Greece was built as recently as 2018, and is privately owned. There’s also a new crematorium in Israel, after the first was burnt to the ground by Ultra-Orthodox Jews in 2007, and which now operates from a secret location.

Despite cremation being largely taboo in Greece today, things were very different some time ago... Image source: Cosmos Magazine

Ironically, it was Greeks (but of the ancient variety) who favoured cremation as a way of honouring warriors slain in battle and repatriating their remains from distant lands many thousands of years ago. (Today, sending human ashes by courier is tricky and exorbitant, in the region of R15K on a popular route, at least double your average plane ticket. Can you imagine the paperwork at Home Affairs? That alone might be enough to kill you.)

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, “cremation [for the Ancient Greeks] became so closely associated with valour and manly virtue, patriotism, and military glory that it was regarded as the only fitting conclusion for an epic life.” Early Romans adopted the habit, and although burial was still a popular option, they are credited with building the first columbaria.

A Roman columbarium.

From Project Gutenberg: 'The Cremation of the Dead' by Hugo Erichsen

Crematory practices in Europe soon declined with the spread of Christianity. Cremation became not only forbidden, but regarded as appropriate punishment for heretics, similar to burning at the stake.

Some people the church considered particularly nefarious, such as the dissident theologian John Wycliffe, were exhumed and posthumously punished with cremation, his body rendered to ash and scattered into a river to prevent any further corrupting influence. I suspect that the flames of cremation and of Hell were seen as one and the same, and in some places, still are.

Cremation conflated with the flames of hell. Painting by Chirila Conchina.

A nice one for the front room? Prints available here for only $53 excl. shipping.

Although there is plenty of evidence for cremation preceding the Ancient Greeks and Romans everywhere from Russia to Australia, it was the Italians who were responsible for the resurgence of crematoria in the modern era. A revolutionary furnace design by Ludovico Brunetti, shown at the Vienna Exposition in 1873, caused a sensation. The world’s first custom-built crematorium soon opened in Milan in 1876 and later the same year in Washington, Pennsylvania, where it was believed that ‘decomposing bodies in local cemeteries were contaminating the water supplies and making the citizens sick.’

This growing movement for the reintroduction of cremation in the 1870s were vocal proponents of the ‘miasma theory,’ which held that cremation would negate the foul air that caused disease. Although advocates of cremation at the time were all for its cleansing attributes and the idea of the purifying flame, they identified strongly as a secular intellectual movement that sought practical alternatives to the problems associated with burial at the time – namely, to “prevent premature burial, reduce the expense of funerals, spare mourners the necessity of standing exposed to the weather during interment, and urns would be safe from vandalism.”

Cremation in the casements of Paris during the reign of the commune. From a fascinating (and free) e-book by Project Gutenberg - 'The Cremation of the Dead' by Hugo Erichsen.

Cremation is undoubtedly a cheaper and cleaner and more efficient way to dispose of bodies.

Local prices for a ‘direct cremation’ (the body straight to the crematorium soon after death, without a memorial service) are around R 8,000 – although curiously, in this industry, you'll get charged according to your socio-economic status, I'm not sure why. Alternatively, you could have a more expensive ‘attended’ or ‘unattended’ cremation, which means the deceased is in a casket at the memorial service, or not.

In Japan, 99% of people are cremated, and elsewhere in the world, especially Switzerland, Canada and The Netherlands, it's way more than 50%. In South Africa and the rest of the continent, cremation is a minority practice. It seems that it is still regarded as sinister, an attitude helped by superstitious misconceptions and conspiracy, the most common of which is that ‘the ashes are all just mixed up.’ But why would they be? Do people think that the dead are not respected in crematoria?

In fact, the process is highly regulated, and each corpse is provided with a unique marker, usually made of a firebrick or a metal that won't melt at 1000 degrees. This is then located amongst the burnt remains, verifying the body which was cremated, which is now about 2.5% of it's former weight. The remains resemble not pure ash but ash mixed with bits of disintegrated bone, which are further ground up in something called a cremulator, which looks just like a giant coffee grinder.

It's a.... cremulator with a cinerary urn! Not a good Pictionary question tho'.

Pic: www.funeralwise.com

For cremation, the deceased is placed in a combustible coffin and loaded up in something called a retort - that's the chamber in the cremator. I'm struck by the lovely choice of word - retort, meaning to "make return in kind" (from Old French retort and directly from Latin retortus, "turn back, twist back, throw back.")

Source: www.funeralwise.com

After the retort is 'charged' with the deceased, incineration takes a couple of hours. Besides ashes and bits of bone, there may be some melted metal from fillings or jewellery that's been missed, casket furniture (those horrible metal handles on coffins) and the odd surgical implant, like the titanium along my shoulder blade. The body organs vaporise, as do breast implants, but pacemakers can cause serious explosions.

Knee and hip replacements collected from American crematoria, about to be buffed up and recycled for re-use.

Picture:from a great little article in the San Diego Union-Tribune

And here's where choice finally kicks in! What kind of 'cinerary urn' would you like? This is definitely something that can be acquired beforehand and stored in the garage. Some people get cremation jewellery made - and here too, you have choice. Heck, you can even choose what colour your 'ash scattering rocket' might be - a projectile which shoots up into the atmosphere and disperses you up there in the clouds. And if you're really feeling sentimental, of course you can mix your ashes with your loved one and get an hourglass made, even though it will not tell accurate time. Now that's classy!

At last, some options! And yes, that's a real 'ash scattering rocket,'

(also known as a Loved One Launcher.)

Who said cremation couldn't get creative? Given all these little bells and whistles, it's a no-brainer why more and more people are getting cremated. It's practical, and a growth industry around the world - just not here, it seems. And hey, it's not just about lack of space, it's about outer space! If you want, you can send some of your ashes into the galaxies where you came from - if that's what you believe.

If you made it to here, give yourself a pat on the back! And thanks for reading and your support... don’t forget - if you like this content or got something from it, consider a donation. Heck, it’ll make you feel fantastic!

Until we meet again, deo volente,

With love,

Sean

Coffin’ Up for Burial Options

Greetings, mortal friend!

When you die and require cremation or burial (a bit like the choice between chicken or veg on a South African Airways flight) - unless your culture has other plans for you, you’ll need a casket or coffin. This is when your loved ones will discover that here in South Africa, we really don’t have much choice.

Wood, veneers and reinforced steel remain the favoured local materials, while a bit of screen-hopping confirms that choice is restricted along a narrow continuum from ‘simple’ to elaborate, from 'less expensive' to 'outrageous' and from 'acceptable' to the kind of thing that would prevent your entry into the afterlife.

Overnight Caskets 'Praying Hands' Monarch Blue Finish With Blue Velvet Interior 18 Gauge Metal Casket

by Overnight Caskets, ON SALE NOW!

Despite the abomination above, a blend of eco-technological innovation, sensitivity to available space, cost-consciousness and environmental awareness have come to bear on the ‘death value chain’ and its associated rituals. Things are changing fast.

I also think that a profound shift in the ‘re-normalising’ of death is occurring, spearheaded by the ‘death positive’ movement and accelerated by the Covid crisis, which has encouraged people to reconsider received ideas about death and dying, including one-time use of expensive caskets. Likewise, people seem to be revisiting the importance of the rituals that accompany death, with so many of them having been ruptured or disrupted during lockdown.

A relative visits a cemetery in New Delhi during the Covid pandemic.

© Shutterstock/Explore Visuals

It feels like images of graves stretching into the distance have become so commonplace that they are losing their affective power. While I understand the editorial instinct for their use, I am becoming inured to them. Like other members of my hodge-podge hybrid South African consumer culture, mostly still riven with the fading remnants of Judeo-Christianity, I have to some extent been inoculated against grief and loss with a distancing dose of medical science and an overriding belief that death is actually optional, until it happens.

Although most of these images place death far away from me, I feel it is actually pretty close, and have never felt my mortality more keenly than right now. I am frequently encountering grief - to get a sense of the depth and scale of this, multiply each death by a factor of eight or nine. I wonder what this collective grief will foment in years to come?

A cemetery awaiting the tragically massive numbers of Brazilian dead in Sao Paulo, May 2020.

© Shutterstock/BW Press

Choices that need to be made by surviving family and friends can be very difficult. Some people however do possess the presence of mind (and enough distrust in others) to choose their own coffin or casket before they die – listen to funeral consultant Mark Wortman describe this in Episode 6 of How To Die, and Cape Town Director of Cemeteries Susan Brice filling you in on local burial practices and our worrying lack of space in Episode 2.

But let’s start with the basics. Is there a difference between a coffin and a casket, you ask? Well, yes – a casket has four sides, while a coffin is hexagonal, with six. Coffins (from the Latin ‘cophinos’ meaning basket) have an anthropometric shape, with a widening at the shoulders and narrowing at the feet – they were once referred to as toe-pinchers. The more euphemistically named casket avoids suggestion of the human form with a rectangular shape. They're also usually able to be opened on a central hinge for viewing of the deceased.

So now that you know, isn't it (not) quite exciting?

© quora.com

Either coffin or casket can also be called a pall, when used to transport a body, although this traditionally refers to a cloth that covers the box. And thus the term pallbearer, someone who carries the coffin, usually in a team of six. I mention this only for etymology nuts like myself, because ‘pall’ derives from ‘pallium,’ a cloak worn in Roman times, and interestingly also relates to palliate, as in palliative care – to ‘mitigate,’ which is then, literally, to cloak.

My own dear father, may he rest in peace, was forever shuffling his designated team of pallbearers, and after the occasional minor fracas on the telephone would be heard to erupt ‘That’s it! Colin’s out, Cecil’s back in!’ This would need to be written down in an increasingly illegible set of instructions for after his death, something that was in frequent focus due to his persistent heart condition and the knowledge that he could pop a gasket at any moment.

Introduced in the U.S. in the mid-1800s, caskets are much more of a one-size-fits-all vibe, as opposed to coffins which must be tailored. Caskets can be quicker to make, apparently. They came into their own during the American Civil War, when they were needed in large numbers (600 000 people died), and lots of bodies required quick transportation.

Perhaps you can see why coffins fell out of favour in the American Civil War.

Image: Uncredited here

In ‘From coffins to caskets: An American History,’ Sarah Hayes writes “It was the violence combined with the scale of death that led to the ‘the beautification of death’ in America during this period, and it was the shift in both name and shape of the coffin that was an effort to distance the living from the unpleasantness of death, and the hexagonal coffins were part of that distancing.”

You might therefore expect your friendly family undertaker to ask if you prefer a coffin or a casket. Jewish tradition meanwhile holds that no metal may be buried with a person, and hence you’ll find only simple wooden coffins with rope handles and wooden pegs in Jewish burials.

The earliest recorded use of wooden boxes for burial date from around 5000 BC in Shaanxi Province, China. Stone or clay, usually baked around the body, were more commonly used across Europe and Asia in ancient times, and then especially for nobility, for kings and chieftains and the like.

Closer to home, I’ve found it difficult to plumb African mortuary archaeologies for evidence of pre-colonial coffin use, and although entire hollowed wooden tree trunks have been used in some parts of the world, there is no record of this anywhere in Africa.

Tree-Coffin from the early mediaeval graveyard of Oberflacht, Germany

Image: Creative Commons Licence, by Andreas Franzkowiak

Note: I am not attempting an accurate historical account of burial in Africa! Besides, as stated by the editors of the Oxford Handbook of Archaeologies of Death and Burial, Liv Nilsson Stutz and Sarah Tarlow, “It is impossible … to draw out any meaningful generalizations from the huge variability of burial practices encountered through time and space across the [African] continent.”

Nonetheless, they provide some fascinating evidence of people being buried in ceramic jars in the western Sahara, and plenty of ornate burial chambers throughout other parts of Africa, usually tied to patriarchal hierarchies. Certainly, burial has always been locally ritualistic, and historically, seems to have also functioned as an opportunity to assert notions of kin, lineage, power and land ownership, to confirm social status, and most importantly, in the pan-African context, preserve the continuity between the living and the dead.

In this sense, the centrality of African belief systems relating to ‘Ancestors’ encourages the idea that comfort for those departing this world is paramount for their entering the next. What I have discovered in my amateur sleuthing is that coffins became widely available only in the 1700s due to a change in English law which had ramifications for English colonies and outposts, allowing ‘common’ people to use them, but I need to corroborate this. I guess coffins became the norm here in South Africa as well, as a departure from using cloth or some kind of equivalent to wrap bodies in simpler ways.

Coffins and caskets have gotten pretty ornate, as can be expected, I guess. An online search for 'African coffins' will result in a deluge of images of the Ghanain variety, popularised by Kane Kwei, a carpenter who started making his own custom 'fantasy caskets' in Accra.

Some things will kill you... ©ADAGP 2013

Kwei had been apprenticed to another local carpenter who had made a cocoa-pod coffin for a local chief. Allegedly inspired by this, when his grandmother died in 1951, he built her a casket in the shape of an aeroplane, and kickstarted a flourishing local industry that remains firmly within the ambit of quaint stereotyping wherever there's wifi.

Cheaper (well, not always, as you'll see) 'fantasy coffins' are the printed and personalized caskets which are now very much a big thing. So, would you like a casket emblazoned in knock-off Louis Vuitton, or do you wish to be known as someone who never had the chance to play for Liverpool Football Club? Both of these can be ordered locally and will set you back around... 65K. But if you're tight, relax, one can be hired for only 45K. Contact these guys.

What a bargain! Liverpool FC casket comes with a picture of Mo Salah at no extra cost!

Pics by Tumi Pakkies, IOL.

Seems like life’s infinite variety is represented in death too.

Nowadays, while so called ‘eco-coffins’ remain a niche offering locally, with a bit of cloth or cardboard, elsewhere wicker, rattan, mulberry pulp, banana leaf, bamboo, wool and cane are some of the things used.

A banana leaf, pandanus and rattan casket from ecoffins.co.

Interesting to me is the shift from a desire to ‘preserve’ the deceased in a metal coffin with sealing gaskets, to the idea of transforming the deceased and returning the corpse to the earth, the dust to dust cycle. In this respect, the hottest ‘new’ material to receive media attention as a coffin material is mycelium, the vegetative or thread like parts of a fungus, called hyphae.

The world’s first ‘living coffin’ is made by Dutch myco-savant, Bob Hendricx. The ‘Living Cocoon’ or Loop coffin accelerates decomposition and reintegration of human remains into the earth, requiring low-impact manufacture containing zero pollutants, and, through myco-remediation, actively removes contaminants from the soil, including heavy metals.

Do you want to be waste or compost? A side of the Loop coffin (which is actually a casket.)

To be honest, I think recycled cardboard does the same job? And it can also be impregnated with spores, which you can buy online.

Although the mycelium coffin accelerates things (around five years for full decomposition), it’s nowhere near as fast as the full-on composting of human remains that is now legal in Washington State, USA. Here it’s called ‘natural organic reduction,’ and for $ 5,500, after no less than thirty days, the compost that used to be your loved one is sent off to help regenerate a local forest, with a small bag provided for your own use.

Composting does away with the idea of coffins altogether, but it feels like we’re stuck with them for a while. Perhaps this is the ultimate solution?

In the meantime, why not make your own? I’ve found a strong tradition of exclusivity and marking-up the price of coffins and caskets, as they make their way from manufacturer to wholesaler to the funeral parlour. If you need them, you can find the handles and rails and things (called ‘coffin furniture’) online, and make your own, like the ‘coffin clubs’ that get together to do so in New Zealand.

Or if space is an issue, perhaps the most cost-effective bet is to make a bulk order of flat-pack cardboard coffins for you and your friends? Why not make it a weekend craft activity, and bring out the paints and glitter markers?

Next post will be all about new cremation options and cool things to do with the ashes ... but please do feed back about this article, especially if any inconstencies or inaccuracies are apparent to you.

Until next time, deo volente, go in peace, go in love -

Sean

Is Dying an Art?

There seems to be some loose consensus that one can - and should, if possible - die ‘artfully’, as some version of a ‘good death.’ But is dying really an art? In this blogpost I look at a few historical precedents and some contemporary thinking about this…

Ars moriendi – The Art of Dying – was originally published in Latin as two related texts, a longer and a shorter in around 1415 and 1450, and gave advice on how to ‘die well,’ according to Medieval Christian precepts. It appeared in over a hundred editions in most Western European languages.

From the shorter Ars Moriendi (all of its pages were printed from single wooden blocks). Here demons tempt a dying man with crowns, a medieval allegory to earthly pride.

It is thought that England’s first printer, William Caxton, interrupted work on another text to translate a French version of the Ars moriendi, which he titled The Art and Craft to Know Well to Die, in 1490, the same year his wife Maude died. This may have been the start of 'death lit,' traceable to the present, a genre that seems to be having a bit of a moment right now, with Atul Gawande's 'Being Mortal' the most obvious (and excellent) example.

'Here begynneth a littyl treatise...' - an extract from Caxton's book.

Originally written by an unknown Dominican friar in the aftermath of the Black Death (which halved Europe's population), and within the profound social, religious and political upheaval of the Middle Ages, Ars moriendi might be evidence of a shift in the way people both experienced and understood death.

It has been recently updated, signalling another shift in contemporary attitudes toward death and dying. The Catholic Church has done so to 'assist terminally ill people and their loved ones deal with death,’ according to this article in the Guardian. 'The Art of Dying Well' website includes animations with a voiceover by the actor Vanessa Redgrave, said to have had a stiff brush with mortality and a wish to die after health complications.

However, several other books, websites, films and other things also called 'The Art of Dying' clog the digital ether.

Is dying really an art? I guess it depends on what you think art is. Answering that feels a little complex. But here goes... Conventionally, art might be defined as skill acquired by experience, study, or observation (Merriam-Webster Dictionary). Art is also a noun, a thing, as in a work of art or artefact, but a type of behaviour too, which can be artful.

Here's a nice one - 'Art is a way of grasping the world. Not merely the physical world, which is what science attempts to do; but the whole world, and specifically, the human world, the world of society and spiritual experience.' (For the full expression of that idea, look here.)

So, whatever art is, it's quintessentially human. As a reflection of human experience, it is subject to notions of value, as good or bad, worthwhile or not. So can dying be an art? Can it be skillful, if it is so utterly happenstance and beyond our control, and also so banal – so normal – that every single one of us does it?

Certainly, the idea of a ‘good death’ has gained in mainstream popularity and become a desired way to go. Perhaps this is a response to a prevailing culture of death denial, of avoiding death at any cost. This too is shifting, I think, as people everywhere tire of the false promises of consumer capitalism and recoil from a scientific tendency for overmedicalisation (is that a Scrabble word?) at the end of life. Still, in our own peri-Western culture, suffused as it is with a plurality of local African and other belief structures, death largely remains taboo and is sometimes simply seen as a failure of life.

From The Lancet, 'The Promise of a Good Death', May 01, 1998

‘What is a good death, and how could you increase your chances of having one?’ was a popular discussion point at the Death Cafes I used to attend. I liked to say my father had one – quick, and in a place he loved, after saying that he was ready to go and had enjoyed a wonderful life. He was 67. Some people pulled in their breath when they heard that. Certainly, I’ve heard of painful deaths, drawn-out deaths, and others. Messy and sad deaths.

In a useful little online essay, ‘The Dangerous Myth of a Good Death,’ blogger and nurse Kathleen Clohessy quotes from Frank Ostaseski’s lovely treatise, 'The Five Invitations: What Death Can Teach us about Living Fully': He says, ‘We treasure the romantic hope that when people pass way, everything will be tied up neatly. All problems will have been resolved, and they will be utterly at peace.’ But this happens rarely. ‘Very few people walk toward the immense challenge of dying and find peace and beauty there… who are we to say how another should die?’

I think this is the risk of calling death an art – that it’s up to the dying person to do it well, or not, imposing some kind of value judgement on it. Think of all those people you’ve met, bleating ‘but oh I’m not creative at all!’ now being informed that their dying was meant to be done with artful skill, done well. Wasn't school hard enough, relationships, all the rest? Now we must excel at death too?

Clohessy continues: ‘Placing expectations on the dying is an easy mistake to make. But when we do so, we limit our ability to open our hearts to what is happening and be truly present with the person who is making the journey in the here and now… When we impose our beliefs about what death “should” look like on someone who is dying, we deny them unconditional love and acceptance they need and deserve.’

So, calling death an art may well make things... well, difficult. This is not to say one should not prepare for death – by all and every means, prepare for the inevitable by talking about it and doing what you can to make it easier for you and your loved ones.

The ‘death positive’ movement, with the redoubtable Caitlin Doughty, possibly the world’s most popular mortician as its high priestess, is a growing community which has some really useful things to say in a manifesto of sorts on their website. The Order of The Good Death, which she co-founded, has a mission to ‘make death a part of your life.’

'Faces of Death' by Landis Blair.

Visit talkdeath.com for '15 Death Positive Artists you Should Know.'

Implicit in most understandings of death however, as well as this idea of a ‘good death’ and dying as an ‘art’ is the veiled assumption that death is some sort of final act.

For me though, death is not just an occurrence. Instead of seeing death as ‘the end,’ consciousness of it provides the means to live a full live. Without wishing to intrude on the province of the suffering, I understand that I am already dying, and that every day death is with me. It is in every cell of skin that falls from me, in each expiring blood cell that perishes within. I’m slowly dying, inside and out. Death surrounds me and I am in it, as much as I am alive and in life. It is in the grief of my friends, in my own grief too. In my own dying I find my vitality. Death sharpens my life.

So it’s a lifelong process, this dying shtick, kicked off at the moment of birth. Carl Jung reminds us that ‘Life is a short pause between two great mysteries. Beware of those who offer answers.’ Perhaps it’s this voracious scientific urge towards a complete system of knowledge that wants to dominate this unknown province, this final mystery – in fact, to cheat it, to perhaps even bypass it entirely - the next big tech 'disruption.'

Gimme a break. I do well to remember that death is a mystery, and something that mystifies. It’s also easy to theorise about and extrapolate upon. Until it happens to oneself.

A good death? An artful expiration? If you really must have one, then, to paraphrase Dr Kathryn Mannix, a palliative care doctor and author, if you want to die well, then first - live well.

That’s about as much as one can do, I think. But what do you think?

Mortal Melodies Vol. 1

Mortal Melodies to hum while you’re still drawing breath… Some you may know, some you may not…