Faces of Death, Faces of Life

Greetings, mortal friend!

So, ever been sent an unsolicited death pic?

I have. It was sent not long ago by the daughter of a friend, a picture of someone on her deathbed whom I'd come to know on the last leg of her earthly journey. We'd done a fair amount of laughing, sighing and shaking and nodding of heads together, and talking about the cancer, and the picture was intimate evidence of a life that was now finally over. It was sent with trust and love. Here she is, it said, but she's gone.

Lately it got me thinking about other images of the dead I've seen, specifically about death masks. The first time I heard about death masks was when I learnt that the one made from Cecil John Rhodes’ cooling visage had been stolen from the very room he died in, in what is now the Rhodes Cottage Museum in Muizenburg.

But one of the nifty things about death masks is that once an impression is taken, any number of casts can be made - some have become commercial items. An edition of Rhodes' death mask by the artist John Tweed sits in the National Portrait Gallery in London, donated by the artist in 1914. Although it was made on the 27th of March 1902, it looks like it could have been made yesterday.

C.J.R.

Image © National Portrait Gallery

It seems strange to see this powerful man, once celebrated, now reviled, at such close quarters. Can you judge a person by their face? I find the protuberant lower lip slightly unexpected, notice the architecture of the jowls and the serenely closed eyes in death, as well as the variegated geography of his brow. It’s almost like watching someone asleep, and slightly transgressive, this feeling of stumbling across someone’s face in private repose. The artefact comes skin-close to the life of a man whose breath has just left him forever. No wonder it was lifted by a thief. It feels like it exudes some kind of aura. I wonder where it is today?

Death masks seem to present a verisimilitude no portrait could express, in all the detailed contours they present. Take this one for example, of Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre, French statesman, lawyer and provocateur, a key figure of the French Revolution, who was beheaded in the Place de la Révolution on the 28 July 1794, aged 36. A harried man at the time of his death, executed in front of a large crowd, the mask somehow conveys a resigned sense of peace and beauty, I feel.

M.F.M.I. de Robespierre

Image from 25 Death Masks of the Famous and Infamous

Next up is not a death mask but a life mask, of Abraham Lincoln, made around five years before he died, in 1860, by Leonard Volks.

Able Abe

Image via Internet Archive

It's interesting to compare it with the one made just before he was assassinated, to see the visible toll his life had on him.

But there was something else going on - you'll notice a droop on the right hand side of the face, and a slackening of his lower lip. Modern doctors say this reveals something called cranial facial microsomia, and others, such as Dr. John Sotos, a cardiologist and rare-disease expert, go further, pointing to facial evidence of a rare, cancer-causing genetic disease called MEN2B (although this sounds like a silly male response to #MeToo). It is now believed by some that Lincoln would have died of thyroid cancer if he hadn’t been shot. (Modern day presidents like Mr. Obama, on the other hand, get to be 3-D printed.)

The poet John Keats, who died from tuberculosis two hundred years ago, on 23rd of February, 2021, aged only 25, is another example. An enamoured collector bought a death mask of his at an auction for £ 12,500 recently.

Death mask of John Keats

Picture by Nik Wheeler, Alamy.

A common use of death masks was to act as a kind of artistic biographical benchmark. In Keat’s case, two masks were made from the same mold made after his death, one of which was used by the artist Joseph Severn to paint a portrait. Although both masks were lost, a secondary impression was made by Charles Smith and Sons, of which an estimated nine copies remain. Keats also had a ‘life mask’ made five years before his death. Comparing the two, one immediately notices the physical wasting that accompanied his illness, and how much thinner his face is.

Life mask of John Keats

Picture: Murdo McLeod, The Guardian

Death masks seem de rigeur for a certain type of person at a certain time in history and were often used for posthumous portraits. Without any fanfare, a newspaper report from as far away as the Philadelphia Times that chronicled Rhodes’ death baldly states, ‘a death mask will be taken,’ as if this is a formality, in the vein of ‘regret no flowers’ at a funeral.

This is why images for any number of famous dead white men of yore are available online: Napoleon Bonaparte, Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson, Oliver Cromwell, Ludwig von Beethoven, James Joyce, Martin Luther… you get the picture. It’s like a type of morbid gallery, each of whom have their eyes closed. They can’t see you see them. (The biggest collection is the Laurence Hutton Collection of Life and Death Masks at Princeton University, which you can visit online.)

One of my favourite masks is of the outlaw Ned Kelly, whose violent life seems to so at odds with this quietened face, which still bristles with characterful evidence of a hard life.

Ned Kelly

Image from 25 Death Masks of the Famous and Infamous

Death masks can be hot property, and not just in Rhodes’ case. When Napoleon died (why on earth isn’t he just called Bonaparte? Don’t people like saying Bonaparte?), also two hundred years ago, incidentally, on May 7th 1821, even though he had been exiled and disgraced, those around him were quick to realise the financial potential a death mask might have for his many admirers.

His is one of the most prolifically copied death masks in the world, partially because of the fact that the surgeon who claims to have made it, Dr. Francesco Antommarchi (although he was challenged in court by Napoléon’s English Surgeon, Francis Burton, who claims Antommarchi stole a mask he had made for the Countess Bertrand) was an avid traveller who commercialised reproduction of the mask and took it with him all over the globe, which is why today, Bonaparte (I refuse to call him by his first name, it’s like referring to James Joyce as ‘James’) peers from countless bookshelves. Trouble is, there are at least eleven versions, with so many discrepancies, that the Fondation Napoléon in France has had to verify them.

The Bertrand-Malmaison Mask of Napoléon Bonaparte

Photo: Creative Commons License

Predating these distinctly life-like impressions, however, were death and funerary masks made for other purposes, dating back into early Egyptian times, when a death mask was deemed essential for any wandering spirit needing to locate the body it had departed from. In some African tribes, it is alleged that death masks endowed the wearer with the life-force of the deceased and was a powerful shamanic tool to maintain connection with the spirit world.

In the Middle Ages the ritualistic aspect waned and as technologies emerged which enabled faithful copies to be made, death masks took on a more secular aspect, both as a physiological record and physiognomic data, and as a way to display deceased people of renown to a curious public. Then too, before the invention of photography, death masks were apparently used by law enforcement agencies to record the physical traits of unclaimed bodies.

Two gentlemen preparing a death mask

Picture: Wikimedia Commons License

Like Bonaparte’s death mask, the American gangster John Dillinger's mask aroused great interest and skirmish. It can be studied on the US Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Artifact of the Month page, along with the death mask of fellow gangster Charles ‘Pretty Boy’ Floyd. Although the making of death masks had all but petered out by this time by the early 1930’s, it was still not uncommon.

Death mask of John Dillinger, on the FBI's 'Artifact of the Month' page.

Dillinger was shot and killed in what the FBI call a ‘confrontation.’ According to the FBI case files, “Every politician and his friend in Chicago crowded into the morgue for the morbid purpose of viewing Dillinger’s remains [....] Great confusion existed at the morgue for several days, inasmuch as there were thousands of people who attempted to gain admission to view Dillinger’s body.”

Police departments inundated the FBI with requests for copies of the mask, and once it was decided that this was too onerous, permission was given for trainee agents to make their own copies from the original while studying at the FBI National Academy, as part of a forensic modelling course, which is still in existence today. “As a result,” cautions the FBI website, “countless copies still exist and are sometimes auctioned online as originals.” Note the damage to the face caused by the ‘confrontation.’

Harold May of the Reliance Dental Manufacturing Co. at work creating the death mask of Dillinger’s face at the Cook County Morgue in Chicago to demonstrate the quality of the company’s plaster.

Picture: Chicago Tribune

Perhaps one of the most recognisable faces in the realm of death masks, not only incredibly popular in its day but also because her mask was repurposed many decades later, belongs to l’Inconnue de la Seine, or The Unknown Woman of the Seine.

This impression was apparently taken from the unidentified body of a young woman recovered from the Seine in the 1880’s, after news of her ‘euphoric’ expression spread all over the city and she'd become a popular fixture in the morgue, which was open to the public. (Any plans for the weekend darling? Should we take the kids over the the morgue?)

It is speculated that she was one of many sex workers who took their own lives by drowning. There is some doubt over this - some say it’s impossible someone recovered from the river would be in such condition. Nonetheless, provenance aside, the tranquillity of her features inspired many Parisians to reconsider the moment of death not as agony but as bliss, and her face became an influential ideal of feminine beauty, compared to the Mona Lisa.

According to an article about her in Wikipedia, the critic Al Alvarez wrote in his book on suicide, The Savage God: "I am told that a whole generation of German girls modeled their looks on her.... the Inconnue became the erotic ideal of the period, as Bardot was for the 1950s. She was finally displaced as a paradigm by Greta Garbo."

l’Inconnue de la Seine

Photo by Albert Rudomine, 1927

Her death mask was copied en masse and has sold extremely well and is still in production by Atelier Lorenzi of Paris, available for €156 at the time of writing.

And in an ironic twist, given her alleged origin story as a victim of drowning, she was both an obvious and a somehow neutral choice for the model of first aid mannequin Resusci Anne, a CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) doll still made by Laerdal (order one here) and used the world over since 1960, and is hence known as ‘the world’s most kissed face.’

Isn’t the internet amazing? One of my cherished sites of yore, when the ‘net was a different place entirely, was rotten.com, which shamelessly promoted itself as the ‘dark underbelly’ of the web. Alas, it is no longer. It took actual courage to click on a link here, after reading a description of the image – things like ‘unfortunate incident in a Tokyo train station.’ What you see you can’t unsee.

Still, it seems like images of death, as much as death itself, are taboo. It’s not done, to stare. I would hazard that many people have not seen a dead body. Why? Death is hidden and death is threatening. Yet death is inevitable and serves to sharpen an appreciation of life, in my experience. The photos I’ve seen online, mainly in the archives of American police departments of ‘John and Jane Does,’ unidentified bodies, attest to the fragility of life, how it is gone in an unexpected breath.

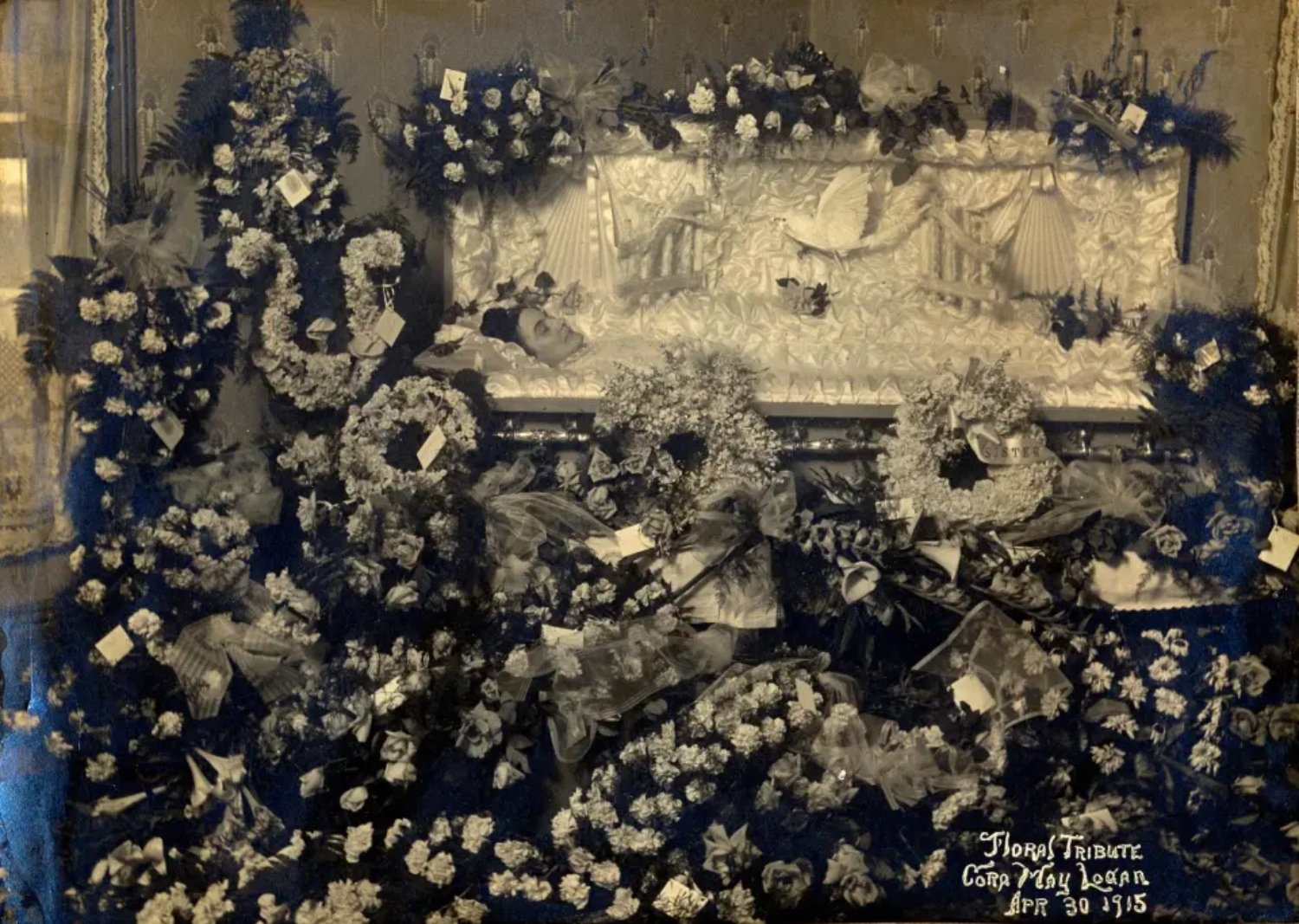

Although Covid-19 has, in my opinion, altered our relationship with death, in other times death might also have been more familiar, like during wars, for example. In the early days of photography, for instance, the Victorians used the nascent technology to capture images of their dead as a memento mori, a keepsake for the living.

For you to remember her by.

Photo Credit: News Dog Media

Still more eloquent is the fairly recent morgue photography of people like Jeffery Silverthorne, who visited the Rhode Island State Morgue in the 1970s. Then fast forward to today, when we have the iPhone and its ilk, ready for a quick and sometimes illicit snap at the deathbed. This too is testament to an evolving relationship with death, I feel, and perhaps allows us to share our grief. ‘iPhone Death Portraits’ occasioned a recent piece in the New York Times.

And finally, dear reader, if all of the above hasn’t quite quelled your morbid curiosity, you could always take a little browse through murderpedia, if you still have time on your hands – because none of us, after all, know exactly how long there is to go.